On the way in from the garage tonight, I passed one of those avery labels from when I first visited my parents in the Intensive Care Unit. Stuck on the cabinet by the door, it was a reminder of the early days following their wreck. Eventually the nurses just let me in without requiring the sticker that showed the patient name and room number.

Dad had his ups and downs consequent to the frailty of age, but he came through just like he said he would that day about a week ago when we talked. He was still alive when I put the sticker there after a visit and we had hope that he’d pull through.

“I’m not concerned, I know I’ll get out of here one way or another,” he said, with a smile and the raised eyebrows of mischief. He wasn’t afraid of dying and had set his limits to what level of heroics he’d endure before calling off the efforts and let nature take it’s course.

A necessary trip took me away, during which his iffy recovery transitioned to an abandoned effort at his direction. By the time I returned, he was at the end. I stayed with him past midnight, only leaving after I’d made the mistake of staring at his hand on the bed rail and remembering what that hand had done on my behalf over the years: held me. Calmed me. Taught me. Fed me. Acknowledged me.

That put me in tears so I left rather than lay that on him. He was pretty busy winding down. It was fair. He’d done the same for me.

After a serious accident in an ironworker shop I was pretty busted up, possibly enough to rival some of his hospitalizations. He came to visit, but before he could enter the room he cried it out downstairs out of sight. No one wants to see their child be in such a serious state, but he also was considerate that the visit was to be a boost to the patient rather than an endulgence for his own feelings. He was a visitor I actually looked forward to. My new wife, who liked to come in and complain that I was being waited on “hand and foot” while she suffered actually showed up with her calculations showing how much money she’d have made if I’d expired under the dirty steel. Dad was somehow a better visitor.

When I go bedside, I try to do like he did.

His last night was particularly difficult for me because of that hand, his hand. The very one that he used to retrieve a yew tree from flood waters so I could make a bow from scratch. He took a risk in that dangerous river water to get us our promised bow wood. Yew wasn’t off limits in those days.

The bows we fashioned were ugly, but the experience was sweet. I was, after all, an up and coming arrowhead chipper and aspiring arrow maker from shaft to spline.

Dad was 4F, meaning that military service was not an option as it had been for his dad and brothers. But his nature and his pereverence allowed him to fare better than many of them. He was 4F because of that very same hand and an accident when he was a boy.

It could be seen as a tragedy, but one wonders. It could have turned out worse. Someone was looking out for him.

He and another lad found the blasting caps. Forgotten, he kept his in a pocket all day.

https://archive.org/details/blasting_cap_danger

Toward the end of that day, he fished it out for a peek. About that time, a fire truck drove past with sirens blaring and he turned to look. That’s when the cap blew off much of his thumb and the nearest fingers of the left hand.

Had it blown up in his pocket, it’s doubtful I’d be here. Without the fire truck he’d have been blinded.

Why it exploded when it did is anyone’s guess. Maybe it warmed up in his hand.

Ironically, one of dad’s passions was reloading ammunition. Explosion of gun powder is the driving force behind every shot. Apparently he didn’t spook easily.

He also didn’t go hungry because he stayed employed. First, a company called Skookum took him on as a welder, which skill carried him through to retirement when he was a millwright at the steel mill. That job allowed his ingenuity to shine.

I followed somewhat in his footsteps by training to weld and then taking my place in a fabrication shop. For twelve plus years, I worked the trades welding and doing the related tasks: plasma cutting, fitting, layout, burning, etc..

This, despite knowing the risks as illustrated by the time dad got knocked off a 40 foot ladder and hospitalized with broken bones from head to foot, prompting my first hospital visits. Very serious injuries were caused when he came down on those unforgiving track rails.

We lived out in the country, so the drive was long. I bivouacked at his parents house a few miles from the hospital. That allowed me in addition to checking on dad to try my best to transfer from grandpa to myself the knack for winning at checkers by playing him again and again. Everyone else had stopped trying long ago because he invariably trounced them, and I was determined to learn how.

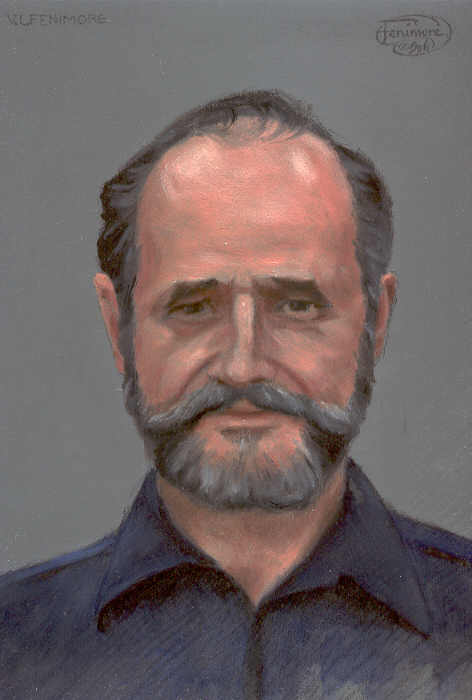

During those days I painted this on the inside of their front entry door:

Dad survived, but it took a long time. Progress was more noticeable after his poor jaw got unwired so he could eat real food.

His attitude was characteristically matter of fact as he weathered the discomfort.

This last hospital stay was the result of an automotive mishap characterized in the newspaper as “driver neglect” but which my brother assumes was the result of low blood sugar and confusion which results from that condition. What dad thought was a freeway entrance was simply the service road for heavy equipment.

He was driving someone who was dependent for transport to a funeral for which he volunteered. It makes sense that my father would live to a good old age but die in the service of someone else.

He had the nature that made him want to fix broken things and get people out of the jams that material things cause with their tendency to fail.

Some might say he was too easy going. But I think there is room for novel styles of dealing with the unreasonable. It is said that his second wife demanded that he miss an anticipated event to watch her daughters child for a mother daughter outing. Rumor suggests that the child was loaded up with prune juice while in his care and created such a diaper crises when returned to the opportunist parent that dad was not again considered a safe baby sitting choice by her.

He was a master of intelligent compliance.

He worked the graveyard shift for a very long time. Between mom waking him up to complain and the need to take care of daytime chores, dad was often sleep deprived. He described it this way, “you have never been tired until you pour your self a cup of hot coffee and when you reach for it, it’s cold.”

This explains how his Jimmy ended up in a field on his way back from work one day.

I have sometimes suspected that part of the anguish he felt when I got hurt so bad was the realization that I was doing the trades on his suggestion. He told me that I could try my hand at being an artist and possibly fail, but I should also get a trade to as he put it ‘fall back on’.

This time, this last time, his hospitalization was made more serious not by the hard realities of an industrial environment alone, but also by the already degrading state of key organs. The ones that could not meet the requirements of his recovery. Every time he faced disaster that resulted in a bunged up body, he was in the act of looking out for someone else, either as a bread winner or just a helpful guy.

He might still be at his house alive right now if he were selfish. But the purpose of life isn’t simply to exist, is it? There are far worse fates than to get into a pickle in the act of looking after someone else.